“I have had my daily Pepys with coffee, every morning. I don’t know what I will do now”: A digital reading of a 17th-century private diary

https://doi.org/10.22394/2412-9410-2023-9-4-177-207

Abstract

This article deals with the issue of digital reading of personal diaries based on the analysis of two projects by Phil Gyford involving the publication of Samuel Pepys’ diary — on a site specifically dedicated to the diary and on the microblogging platform Twitter. When discussing the genre of the personal diary and its publication, generally the problem of privacy and its violation comes to the forefront: it is seen as central to understanding the impressions as well as the experiences of a reader “immersed” in someone else’s private life and experiencing both a feeling of guilt, opposing him/herself to the author/hero, and nostalgia for missed opportunities, which brings closer to the text the view that the diarist himself might have, upon re-reading his/her notes. Consideration of the forms of diary publication on the Internet, which sought to create “a living reading” and assumed a reading model fundamentally different from that of a printed book, allows us to pay attention to other aspects of the reader’s perception of someone else’s personal diary, conditioned by the specifics of the media and everyday practices. Analysis of the image of Pepys himself, of his text, and of the past in general as they appear in the comments of the users of both projects touches upon three main aspects — the influence of media on the perception of the narrative, the framing of the text being read, and the inclusion of the diary in the reader’s everyday life. The comparison of the two projects, which reveals, in full correspondence with Marshall McLuhan’s idea of “the medium is the message”, a significant difference in the perception of the same text, problematizes the already criticized genre definition of the diary and its characteristics. Users’ comments allow us to speak not only about other mechanisms of forming a sense of privacy and closeness to the author, which are considered to be among the most important for defining the private diary genre, but also regarding the issue of privacy: in certain practices of reading personal diaries the angle of “peeping” can change into its opposite — the diary’s interference in the private life of the reader.

About the Author

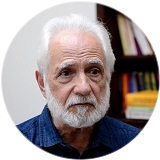

A. V. StogovaRussian Federation

Anna V. Stogova, Cand. Sci. (History), Senior Researcher, Department of Studies in Theory of History

119774, Moscow, Leninsky Prospekt, 32a

Tel.: +7 (495) 938-12-02

References

1. Bayley, S. (2016). The private life of the diary. Unbound.

2. Berger, H. (1998). The Pepys show: Ghost-writing and documentary desire in “The Diary”. ELH, 65(3), 557–591.

3. Buford, L. (2020). A journey through two decades of online diary community. In B. Ben-Amos, & D. Ben-Amos (Eds.). The diary: The epic of everyday life (pp. 425–440). Indiana Univ. Press.

4. Chartier, R. (2004). Languages, books and reading from the printed word to the digital text. Critical Inquiry, 31(1), 133–152.

5. Deotto, P. (2019). Dnevnik kak pogranichnyi zhanr [Diary as a borderline genre]. AvtobiografiIa, 8, 11–18. https://www.avtobiografija.com/index.php/avtobiografija/article/view/188/176. https://doi.org/10.25430/2281-6992/v8-o11-018. (In Russian).

6. Dijck, J. van (2007). Mediated memories in the digital age. Stanford Univ. Press. Foys, M. K., & Trettien, W. A. (2010). Vanishing transliteracies in Beowulf and Samuel Pepys’s diary. In O. Da Rold, & E. Treharne (Eds.). Textual cultures: Cultural texts (pp. 75–120). Boydell and Brewer Limited. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781846158902.006.

7. Hassam, A. (1987). Reading other people’s diaries. University of Toronto Quarterly, 56(3), 435–442.

8. Henderson, D. (2018). Reading digitized diaries: Privacy and the digital life-writing archive. a /b: Auto/Biography Studies, 33(1), 157–174. http://doi.org/10.1080/08989575.2018.1389845.

9. Lejeune, Ph., & Bogaert, C. (2003). Un journal à soi: histoire d’une pratique. Textuel. (In French).

10. McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. Signet Books.

11. Rettberg, J. W. (2020). Online diaries and blogs. In B. Ben-Amos, & D. Ben-Amos (Eds.). The diary: The epic of everyday life (pp. 411–424). Indiana Univ. Press.

12. Rousset, J. (1983). Le journal intime. Texte sans destinataire? Poétique, 56, 435–443. (In French).

13. Wilkins, K. (2014). Valhallolz: Medievalist humor on the Internet, Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies, 5(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1057/pmed.2014.14.

14. Zalizniak, Anna A. (2013). Dnevnik: k opredeleniiu zhanra [Diary: Toward a definition of the genre]. In Anna A. Zalizniak. Russkaia semantika v tipologicheskoi perspektive (pp. 509– 523). Iazyki slavianskoi kul’tury (In Russian).

15. Zvereva, V. (2012). Setevye razgovory: Kul’turnye kommunikatsii v Runete [Network conversations: Cultural communications in Runet]. Department of Foreign Languages, Univ. of Bergen. (In Russian).

Review

For citations:

Stogova A.V. “I have had my daily Pepys with coffee, every morning. I don’t know what I will do now”: A digital reading of a 17th-century private diary. Shagi / Steps. 2023;9(4):177-207. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.22394/2412-9410-2023-9-4-177-207